|

| Students at Saturday oatmeal stout brewing workshop add molasses to the mix. |

Our

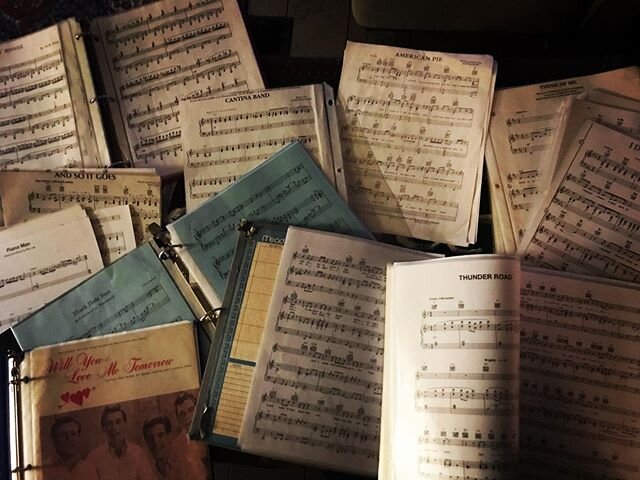

workshop season kicked off Saturday with a beer-brewing workshop taught by Master Brewer Paul Jennings. This was part one of a three-part brewing series Paul is offering at Better Farm this summer (wine making is slated for July 13—you don't want to miss it!), and the focus was on getting a batch of oatmeal stout started.

We used a basic stout recipe for this, and got the first steps completed in one morning. We added yeast the following day, and are now enjoying the process of watching the mixture ferment. We'll be able to carbonate the beer in a few weeks. Here's the recipe we followed:

Ingredients

1 pound dry light malt extract

1 pound oatmeal

1 cup brown sugar

2 cups molasses

2 oz. Keng Golding hops

1 packet Lallemand Windsor yeast

1 1/4 cups priming sugar or cane sugar

1 hops bag for oatmeal

Directions

Bring 2 gallons of water to a boil.

Turn off burner and add bagged oatmeal to the water.

Let sit for 1 hour.

Remove oatmeal from the water.

Add all other ingredients to the water.

Heat the mixture (wort) almost to boiling and simmer for 1 hour.

Bring the mixture to a boil and let wort boil for 1/2 hour.

Add wort to primary fermenter and top off to the 5-gallon mark with boiled water.

Add yeast when cooled. (Temperature should be down to 70 degrees—click here to learn how to

make your own wort chiller, which will cool the wort quickly. The faster you can cool the wort, the better the beer's clarity and flavor, and reduces the risk of contamination).

At bottling time, add priming sugar 3 hours prior.

Some photos of the process:

|

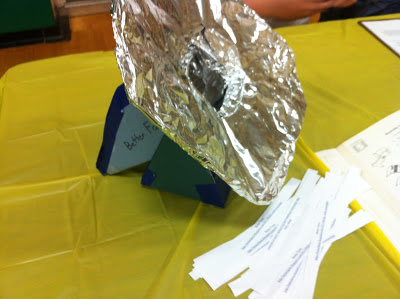

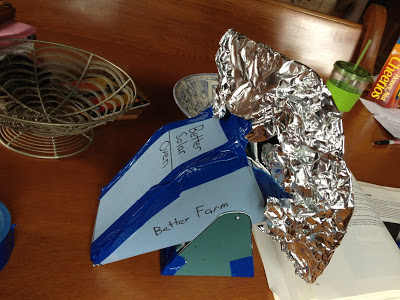

| Primary fermenter, left, and at plastic bin with other supplies like thermometers. |

|

| Pouring the wort into a primary fermenter. |

We'll check back in a few weeks to show you the carbonation and bottling process! If you plan to be in the North Country this Saturday, be sure to sign up for our sauna-building workshop!

To find out more about upcoming fermentation workshops and other educational opportunities at Better Farm this summer, click here.