|

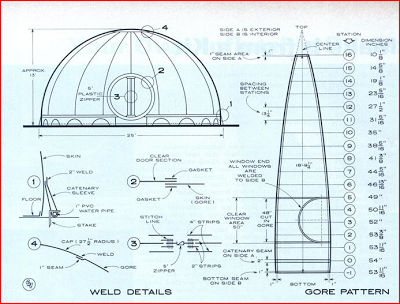

| A simple laundry-to-landscape graywater system diverts water from a washing machine and directs it to mulch basins around plants. Illustration/Elayne Sears |

Originally published in Mother Earth News

By Laura Allen and Cleo Woelfle-Erskine

In the United States, the average person uses about 40 gallons of water per day to bathe, wash dishes and clean clothes. Unfortunately, this water almost always goes straight down the drain. But this “greywater” could be put to good use to irrigate fruit trees and other plants. Greywater refers to all used household water except water from toilets, which is called “blackwater.” Historically, state laws have dealt with water from your sink, shower or washing machine in exactly the same way as water from the toilet — it’s all considered sewage that requires treatment. Consequently, home systems that use greywater for irrigation are sometimes illegal.

However, in recent years, greywater activists have been working to change this attitude and the state codes that enforce it. Now, with more than half of U.S. states facing water shortages and the momentum shifting as some states change their codes, we think greywater reuse is coming into the mainstream. Many policymakers are beginning to see greywater as a valuable resource that — with a few simple precautions — can be safely reused in home landscapes.

For decades, greywater has been a boon to gardeners in dry climates, but using greywater has many other benefits in all regions. Greywater use lowers your water bill, and diverting greywater from overloaded or failing septic systems can extend their life. Reusing water saves energy: Greywater irrigation replaces water that would otherwise be treated to drinking water quality, and it also isn’t treated at the sewage treatment plant, saving more energy. And perhaps most importantly, more efficient water use reduces pressure on scarce water resources — especially in the drier parts of the country, where farmers, individual households and wildlife all face the problem of limited water supplies.

A Simple Laundry-to-Landscape System

The simplest type of greywater use is to collect water in a dishpan as you handwash dishes, and then toss it over your flowerbeds or fruit trees. This is a wonderfully simple, inexpensive way to tap into greywater, but with just a little more effort and expense, you can capture much more water.

One of the easiest and most popular greywater systems is a landscape-direct system that diverts greywater from your washing machine and routes it to mulch basins around trees or bushes. This “laundry-to-landscape” system captures greywater from the drain hose of the washing machine and sends it out to your plants through 1-inch tubing, without the need to alter existing plumbing. You can expect to harvest 10 to 25 gallons of water per load for a horizontal-axis machine, or about 40 gallons per load for a vertical axis machine.

According to Art Ludwig, author of

Create an Oasis With Greywater, the laundry-to-landscape system is the “simplest, least expensive, lowest effort way to get the most greywater out onto the landscape.” The washing machine’s internal pump pushes the water outside through the tubing, so these systems can work without any additional pumps on flat or downward-sloping sites.

Creating this type of system is as simple as installing a diverter valve on your washing machine, attaching and positioning the hose, and digging simple

mulch basins for your plants. The mulch basins provide room for greywater to spread out around the plants, as well as preventing greywater from running off, or creating pools where mosquitoes could breed. The mulch also helps keep grease and soap from clogging the soil. These greywater systems typically cost $75 to $200 if you do the work yourself, or up to $2,000 if you hire a professional. This type of system works best for trees, bushes, and large annuals or perennials.

You can build a landscape-direct greywater system yourself if you’re knowledgeable about plumbing and basic landscaping. A plumber familiar with greywater systems can help install the diverter valve. Or hire a landscaper or plumber who has experience with greywater to install your complete system.

Other Greywater System Options

You can also use a “branched drain” system to send water from your showers and sinks to mulch basins. This system relies on gravity to distribute the water, so it only works if the plants are located below the source of water. Branched drains require little maintenance because there are no moving parts that could break. These systems can be simple or nearly impossible to install — it depends on your existing plumbing. If your garden is above your water source, you can install a pump designed for dirty water (called an effluent pump) to move water uphill in 1-inch tubing.

Greywater can be used with drip irrigation, but needs to be filtered first. Manufactured systems use filters to remove solids, and pumps to send the water into special greywater-compatible drip irrigation tubing. Drip greywater systems can distribute water to more, and smaller, plants, but the filters require regular cleaning and maintenance.

More complicated greywater projects are expensive, complex and require a higher level of maintenance, so they’re best suited for larger applications, such as apartments, schools and commercial buildings. One example of a larger greywater project is Casa Dominguez, an affordable housing development in Los Angeles County, where greywater from the complex’s washing machines is used to water the landscaping plants. Treated greywater can also be used to flush toilets, as in the Mercy Housing Building in Chicago, where 96 apartments flush with greywater.

For home systems, keep in mind that simpler is almost always better. In our experience, the more complicated, high-maintenance systems sometimes fail, while the systems that work best for home use are usually those designed to require minimal care.

Using Greywater Safely

Before using greywater in your yard, there are a few precautions to be aware of. One is that when you use greywater, you’ll want to choose natural soaps that break down in the environment and won’t harm plants. Stay away from any cleaners with bleach or other toxic ingredients. Avoid sodium and boron, which are fine for us, but bad for plants and soil. (See the resources list below for some specific brands of greywater-friendly cleaners.)

It’s a good idea to avoid direct contact with greywater — wash water often contains small amounts of bacteria that come from your clothes or body. Always follow these rules when using greywater at home:

- You can use greywater on edible plants, but only fruit trees or crops such as corn or raspberries, where the edible part is off the ground. Don’t use it to water root vegetables.

- Never store greywater for longer than 24 hours.

- If you reroute your plumbing, install a diverter valve so you can choose when to send water to the greywater system and when it should go into the sewer or septic system.

- Don’t allow greywater to pool up or run off — make sure it can soak into the ground.

Finally, bear in mind that even simple systems will require some engagement from you, your family and your guests. Label pipes and valves so others know how to operate the system, and be sure others know what kinds of soaps can be used. Check mulch basins regularly to be sure they’re functioning correctly.

Greywater in the Southwest

Greywater codes are gradually changing, but considerable work needs to be done before everyone in the United States can use greywater legally. So far, greywater advocates have been most active in the Southwest.

In California, efforts at greywater reform have been mixed, but there have been some recent improvements. Changes to greywater codes began in Santa Barbara in 1989, but for many years it remained difficult to get permits for greywater systems in California. Most people using greywater ignored the codes, and unpermitted systems became the norm. At one point California hosted an estimated 1.7 million illegal greywater systems. In 2009, California revamped its greywater codes. The new code allows simple laundry-to-landscape systems without a permit, but requires permits and inspections for most greywater systems.

Arizona may have one of the best models for greywater use. “We conducted a study in southern Arizona and found that 13 percent of people were using greywater, all illegally,” says Val Little, director of the Water Conservation Alliance of Southern Arizona. “Since we couldn’t inform them how to do it properly due to the restrictive state code, we worked to create new ‘performance-based’ regulations. Now, if people follow the guidelines, their system is legal.”

In Arizona, there are no fees, permits or inspections for systems that use less than 400 gallons per day and follow the guidelines (larger systems require permits). In the decade since the code change, state-wide tax credits, water district support, free classes and online pamphlets have promoted widespread greywater use, without any reported problems. Texas, New Mexico and Wyoming have since created similar performance-based codes.

Other State Greywater Codes

If you live in the Midwest, South or Northeast, your state most likely either has no specific greywater code, or else greywater is regulated along with septic systems. Legal reuse can be costly, requiring small leach fields or expensive engineered plans.

Here are a few examples of state greywater regulations. (Keep in mind that greywater codes are complex, and updated frequently, so keep your ears open for what’s happening in your state. Find a good list from the

Oasis Design Greywater Policy Center.

- Florida bans outdoor greywater use, but allows indoor use for flushing toilets.

- In Georgia since the last drought you can legally carry greywater in buckets to plants or build a complex greywater system (with a permit), but you can’t get a permit to build a simple greywater system.

- Washington’s new code allows some small systems without a permit, but imposes stringent requirements on other systems.

- Oregon’s proposed code mandates an annual permit fee — a move that is already generating opposition.

If you’re not happy with the greywater codes in your state, contact your legislators about changing them! There are many benefits to be gained from moving toward less restrictive greywater codes. With codes in place supporting safe and simple reuse, greywater could reduce U.S. water use by 600 million gallons per day by creating a “new” source for non-potable uses.

Code change also opens up a new job market — every plumber and landscaper could potentially build simple greywater systems for their customers, and there should be plenty of demand for inexpensive, landscape-direct systems.

Building your own simple system is even more affordable, and as common-sense code changes make it easier to tap into greywater, recycling your water is looking more and more like a smart idea. Get ready to load up your washing machine and watch your garden thrive!

Greywater Resources

Books, Kits and Parts

Oasis Design offers parts and

free instructions.

Clean Water Components sells complete kits to build your own greywater system.

Create an Oasis With Greywater by Art Ludwig

Greywater Policy Issues

Greywater Action

Oasis Design Greywater Policy Center

Greywater-Friendly Cleaners

Read the ingredients and look for products that contain no salt or sodium, boron or bleach. For water softeners, avoid sodium-based products. Choose a potassium-based one instead.

Laundry detergent: Oasis or ECOs detergents

Dish and hand soap: Oasis All Purpose Cleaner, Dr. Bronner’s, any natural liquid or bar soap

Body products: Look for low- or no-sodium options. Products from Aubrey Organics are some good choices. Check the ingredients lists of other products at theEnvironmental Working Group’s

Skin Deep Cosmetics Database.