New York State's Day-Old Pheasant Program distributes 46,496 day-old pheasant chicks to qualified applicants across the state who agree to raise the baby birds to eight weeks of age and then release them. We'd like to get

Better Farm involved, which means we have to construct a fly pen for the pheasants and create other crucial accommodations. To make the research part simpler for those of you also interested in getting with the program, here's a handy outline of what we've learned about raising these beautiful birds.

(Editor's Note: To ensure their best chance of survival in the wild, it's very important to give pheasants PLENTY of natural surroundings to grow up in (brush, grash, bushes, branches)—and to release them no later than when they're eight weeks old.)

Brooding

The brooder house for pheasant chicks should be weather tight, free from drafts and rodent proof. It can be designed for the birds or part of another building that can have a penned-in portion.

Young pheasants are very delicate and your brooder must be set up correctly or you may encounter problems. Clean and disinfect your brooder house at least two weeks before the chicks arrive. The best litter to use on the floor is chopped straw. Pheasants seem to like to eat wood shavings. If the chicks have access to wood shavings, they will eat them and die. Sand or newspaper is not recommended as litter. If brooder paper (a coarse, rough paper that allows chicks to keep their footing) is not available at your feed store, burlap works very well also. Do not use newspaper as the chicks will not be able to get a firm footing. Remember to remove the burlap or brooder paper after the chicks are about one week old.

Heat Lamps

Heat lamps are the easiest to use. Be sure to have at least one 250 Watt infrared bulb for each 100 chicks you plan on starting. Make sure to get the bulb with a red end, as it won't be so bright and will help control cannibalism. Hang the heat lamp from the ceiling, about 18 inches from the floor to the bottom of the lamp.

Ring/Draft Shield

Use a ring or draft shield to confine the chicks for the first 5-7 days the chicks are in the brooder. Cardboard about 14-18 inches high can be bent to make a ring or circle. A kiddy pool will work too! A circle with a diameter of 4 feet will be sufficient for 50 chicks (with the heat lamp in the center). This shield helps cut down on the drafts on the floor.

Your brooder house should be big enough to allow 3/4 of a square foot per bird. Pheasants tend to be very cannibalistic, so don't overcrowd them.

Use at least one 2-foot long feeder for each 50 chicks. Also, 1 one-gallon waterer for each 75 chicks. Use a waterer with a narrow lip (1/2 inch or less) or fill the water trough with marbles so the chicks can't drown.

From the time chicks arrive until they are six weeks old, they should be fed a 30% protein medicated gamebird or turkey starter feed. The best medicated started feed contains 1 lb. Amprolium (a coccidiostat) per ton of feed. The feed should be in crumble form.

Introducing Chicks to Their New Home

When the chicks arrive, remove them from the box, dip their beaks in the water, and put them under the heat lamp. Most losses occur because the chicks do not start to eat or drink. Never let your chicks run out of feed or water. The chicks should form a circle around the heat lamp. If the chicks bunch up directly under the heat lamp they are cold. Lower the lamp, and add more bulbs, or further draft-proof your brooder house. If the chicks spread out too far away from the brooder and pant, etc...they are too hot - turn off one of the bulbs, raise the heat lamp, and perhaps open a window during hot weather.

Inspect the chicks often during the first week - especially at night during the first few nights. Chicks often die from piling (from being too cold) during the first or second night.

After the chicks are 2 or 3 weeks old it is a good idea to allow the chicks to range outside during the daytime. Wait for a warm sunny day and open the brooder house door into the pen. The pen must be covered and enclosed with one inch hole chicken wire to prevent the chicks from escaping. The pen should be large enough to allow 1 - 2 square feet per bird. Drive the chicks back into the house late each afternoon. Continue to turn the heat on each afternoon. Discontinue operating your heat lamp during the day once the chicks spend each day outside. Continue to turn the heat on each night until they are 3-4 weeks old (depending on how cold it is outside). After the birds are 4-5 weeks old, they will need a bigger pen. You should always be on the lookout for cannibalism. The first evidence you will see will be blood on the wing tips and tails of some of the smaller birds. Don't expect it to just go away—instead, it will just get worse. Add branches and alfalfa hay to the pen for the birds to peck at and play on - this will help. You may have to trim the top beaks on your birds to curtail the problem. A pair of fingernail clippers will do - trim far enough back just so it bleeds a little. This can be done as early as 2 weeks old and may have to be repeated.

Pheasant Pen

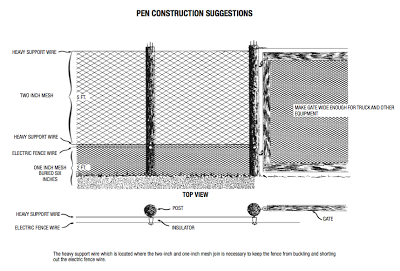

One of the most expensive requirements on a game bird farm are covered pens. It is important to build your pens in such a way that they will do what they are supposed to do. ie keep the birds in and predators out. Other considerations are 1) cost 2) long life 3) ease of construction 4) resistance to bad weather. Below is a covered pen that incorporates many of these desirable characteristics.

Basic Layout

- A pen of 144' x 96' conforms to two rolls of toprite and can hold 700 hens with peepers, or 500 cocks with peepers, or 600 hens and cocks with peepers.

- Pheasants require 25 square feet of pen space per bird for proper flying. Building a bigger pheasant pen is better than building one too small.

- Keep building costs to a minimum by price shopping for new materials or reusing chicken wire, fencing and lumber.

Use pressure treated lumber or locust for the main posts. Choose materials that are resistant to bad weather and outdoor durable.

-

Locate the pheasant pen in an area with adequate shelter and shade access. The more natural cover available, the safer young pheasants will feel, which results in less cannibalism.

Design the pen with gates or doors of sufficient width and height to allow for easy feeding, watering and catching of young chicks.

Posts

These posts should be set equidistant from each other around the perimeter of the pen. It works out that the posts should be 12 feet apart. The posts should be 10' long. They should go into the ground 3' and extend 7'.

Wire

The four sides of the pen should be covered with galvanized-after-weaving wire - 1" mesh - either 18 or 20 gauge. This wire should be buried at least 6" and flared to the outside underground. This prevents animals from digging down under the pen. The wire should extend up to the sides of the pen to the tops of the posts.

#9 Wire

A standard #9 galvanized wire should be strung around the top of the poles around the perimeter of the pen. Another strand of #9 wire should be strung the length of the pen equidistant from the two sides. Two #9 wires should be strung widthwise splitting the pen in thirds. These #9 wires will support the roof. The poles to which the #9 wires is attached should have "dead-man" poles for support. This will prevent the poles from pulling in.

Toprite

Over the top of this grid put two connected rolls of 150' x 50'

toprite netting. The netting should be connected to the four corners first to make sure it is square. It should be pulled over the edges and attached to both the #9 wire and to the wire sides. DO NOT attach the netting to the #9 wire running through the pen. You should hog-ring the #9 wire to the toprite in the inside of the pen about every 5' to prevent ripping in the wind. At the junction of the #9 wire in the middle of the pen, put brace posts made of 2" x 4" material. They should be tall enough (10 to 12 ft.) to make the pen tent-like in appearance. On the top of the 2" x 4" add a screw-in eyehook, run the #9 wire through, then close the eyehook. This pen is designed to be lowered in case of wet snow or icy conditions. In case of foul weather, simply take down the 2" x 4" poles and let the toprite down. Even with the birds inside, they will move to the edges of the pen. This pen is economical as you have fewer posts and #9 wire then most pen designs. I purposely avoided the subject of gates, feeding, watering or catching birds, as each farm has is own situations.

Building Instructions

Information gleaned from

MacFarlane Pheasants, Inc.,

ehow.com,

GardenWeb.com.

To learn more about our adventures with pheasants, check out this link:

The Freeing of the Pheasants