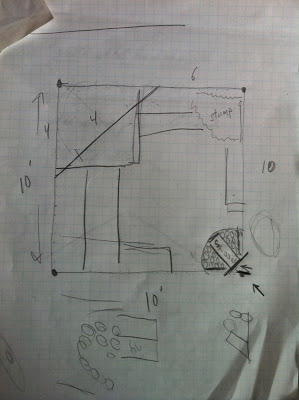

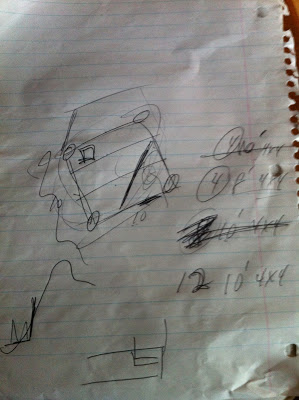

A keyhole garden is a raised, circular garden with a compost basket in the center, which gives it a keyhole shape when viewed from above. Keyhole gardens are often used in dry climates where the topsoil is very thin and rainfall is infrequent because it can survive with very little watering due to the compost basket.

The keyhole garden was initially developed in Africa by humanitarian organizations in order to create a sustainable food source that would be relatively unaffected by climate.

According to the BBC, “three keyhole gardens can feed a family of 10”for an entire year.

The placement of the compost basket makes the garden easily accessible and allows the layers of the garden to retain moisture and nutrients that run off from the compost basket. Keyhole gardens can be constructed with recycled materials, making them ideal for people looking for sustainable alternatives to traditional gardens. The soil of keyhole gardens can be constructed of mostly compost or the traditional layering method can be used.

To build a keyhole garden, you need to first mark the outline of the garden and place four corner posts in the center; the corner posts will be used to construct the compost basket. The outline of the garden will dip into the center on one side so the compost basket will be easily accessible. The basket is encircled with rope and can also be thatched to allow water poured into the basket to seep out into the rest of the garden. For the first layer of the garden, you can use iron scraps such as empty food or soda cans, dry animal bones, or fist-sized stones. These materials provide drainage in the rain and minerals to the soil. The first layer can be covered with soil or compost, thatching grass to retain moisture, and wood ash to provide potassium. This layer can be covered with another layer of soil or compost. Each layer should slope downward from the basket so water can flow into the soil. A thick layer of mixed soil and dry manure can be added on top and stones should be added to the outer wall as the layers grow taller.

Although keyhole gardens can produce all-year round depending on climate and what types of plants are planted in the garden, in the winter, plants should be protected by using either thatching grass or an old carpet that can be removed during the day to allow them to receive sunlight.